Author and journalist Matt Anniss speaks to one of Bleep’s lesser known legends – Ability II

You’ll struggle to find many better ‘bleep and bass’ releases than Ability II’s Pressure EP. It’s perhaps not as well known as the records that defined the style – think Unique 3’s “The Theme”, Forgemasters’ “Track With No Name”, Nightmares on Wax’s “Dextrous”, Sweet Exorcist’s “Testone” and LFO’s peerless “LFO” – but it’s rightly regarded as one of the sound’s seminal releases.

To this day, it still sounds phenomenally good – as Major Problems’ new re-release so emphatically proves. While many bleep and bass anthems have not stood the test of time, “Pressure”, and the even better B-side, “Pressure Dub”, sounds as weighty, alien and intoxicating as they did way back in 1990. Given the enduring quality of the record, it’s something of a surprise that its creator, a producer called David Duncan, isn’t more widely known. But then the Pressure EP was his sole release of note, and in the years since he’s all but vanished from the music scene.

Duncan, though, seems re-energised by the renewed interest in “Pressure Dub”. Before this Major Problems reissue, Richard Sen included the track on his superb retrospective of early UK acid house and techno, This Ain’t Chicago. The former Bronx Dogs man also made a cover version of his own, Songs of Pressure, which was released on Emotional Especial back in 2014. “I was flattered when I heard that,” Duncan tells me over Skype from his Copenhagen home. “I do think it’s an honour if someone makes a record like that, because it means that ‘Pressure Dub’ really meant something deep to them.”

The Pressure EP

The Pressure EP may have been the enduring highlight of David Duncan’s relatively short production career, but his musical journey started much earlier. Like many of his contemporaries in the bleep and bass scene, he was turned onto electronic music by hearing electro for the first time in the early ‘80s. “I was part of a breakdance crew, and that really got me into dancing seriously,” he reminisces. “I used to go up to the [organized dance battles at] Rock City in Nottingham quite a lot. Leicester itself had quite a vibrant scene as well – there were quite a few crews. It was really cool, and there was a lot to do connected to the electro sound.”

https://youtu.be/14DdZhwAIQA

The links between Electro and Bleep can be heard on numerous records from the period. It still seems to surprise Duncan that so many of his contemporaries had a similar musical education, though. “It’s quite strange, that,” he muses. “I guess that’s why the music we made was very much its’ own thing. We were taking something from that, and then putting these deep, deep elements with it.”

Unlike some of his close friends from the techno and house scenes, Duncan didn’t wait to become a club-going adult to try his hand at music production. From his early teenage years, he had a small studio set-up in his bedroom. “I was always interested in electronics,” he says. “I liked making gadgets and stuff like that. Electronic music was just a progression. It really grabbed me, partly because of my interest in electronics, but also because you didn’t need to be a trained musician to do it. You could just pick something up and create this mad sound, basically.”

Duncan’s rudimentary set-up “one of the DX series” of Yamaha keyboards, a four-track tape recorder, a sequencer, and later a Roland SH-101 mono-synth – went with him when he moved to Leeds in 1989. He’d gone to study at the Northern School of Contemporary Dance, but found himself immersed in the city’s vibrant party scene. “Being at the dance college probably pushed me towards going out in certain places, which also happened to be where the guys from BASSIC Records were going out as well,” he admits. “Dancers always went to where the real party was. That’s how the two scenes were linked together, and really how I got involved with meeting DJ Martin, Mark Millington and others.”

At the time, there were quite a few regular spots that Duncan and his dance contemporaries would go to hear the freshest new sounds – The Warehouse, Nightmares On Wax’s Downbeat parties at Ricky’s, and a forgotten place called Mr Craig’s – but the party really only started when they got to the “Blues”: illicit, unlicensed late night venues that were once a thriving part of Britain’s Afro-Caribbean communities. “When I moved to Leeds, I went to live in Spencer Place, and that was right in the heart of where the Blues [clubs] were,” Duncan fondly remembers. “After the club, you always used to go to the Blues, and they were always rammed. All weekend, there would be different Blues running, and depending on what style you liked, you’d move from on to another. Those were really good times.”

https://youtu.be/W8QfNMNm9CI

The “Blues” were not unique to Leeds – Sheffield, Bristol, Birmingham and other places with large Jamaican communities also had plenty – but they really helped fuel the “Bleep and Bass” boom in Yorkshire’s largest city. Musically, each “Blues” had its own particular vibe; while some would play straight-up party jams, others would serve up purely reggae on custom-built sound systems. By the summer of 1990, there were even “Blues” that focused on Bleep and Bass, as well as the more breakbeat-driven variations of the sound popular down south. “You’d go there and you’d hear different things, almost all of which would have really heavy bass,” Duncan enthuses. “At one point I had my studio in the basement of the place I was living in, so I could come straight back from the Blues and get into the studio. I’d bang through track after track that way, such was the inspiration from what I’d heard at the Blues.”

He wasn’t alone in that respect. Gez Varley once claimed that the heaviness of the sub-bass on “LFO” was inspired by a desire to impress dancers at their favourite “Blues”, whose enthusiasm could be sparked by particularly deep, rich basslines. “A lot of the Leeds DJs and producers would be out and about, and we’d bump into each other all the time at the Blues,” Duncan says. “We’d all be doing our own thing but we were inspired by similar sounds and experiences. The Blues was bound to influence us all that way.”

Leeds most influential selector of the period, DJ Martin (real name Martin Williams), could regularly be heard spinning at the “Blues”. It was through Williams hearing one of his demos – via a mutual friend – that David Duncan was given a chance to record what would become the Pressure EP. Williams is undoubtedly one of bleep’s unsung heroes. Aside from being resident DJ at The Warehouse, he was also a hugely talented studio engineer. He co-produced “LFO” to help his young friends Mark Bell and Gez Varley, and in early 1990 joined forces with Crash Records to launch BASSIC: a studio and record label dedicated to championing Leeds-made techno.

By the time Williams got in touch with David Duncan, BASSIC had already scored two significant bleep and bass hits: Juno’s “Soul Thunder”, and Ital Rockers’ “Ital’s Anthem”. The latter was the work of sound system freak Mark Millington, later to find fame on the dub scene as Iration Steppas. It wasn’t long before Duncan and Millington became close friends.”We’d go to events together, and later go out and do PAs at clubs,” Duncan reminisces. “I’d also sometimes support him as a DJ when he was doing his sound system parties. We had a lot of fun together.”

“We just kept tweaking it to try and make it as dubby and deep as we could. We’d keep doing this until we ended up with a sound that we liked. It was all just a slow process of creating, tweaking, and creating more.”

When Duncan finally got into the BASSIC studios with ‘DJ Martin’, it didn’t take long for Millington’s influence to come through in the music they were making. “Pressure Dub really came from Mark’s influence,” he admits. “That’s where the deep and spacey elements came from, I think.” Astonishingly, the two tracks showcased on Duncan’s sole Ability II 12” took almost six months to produce. In hindsight, you can hear it; by bleep and bass standards, both “Pressure” and its more celebrated B-side, “Pressure Dub”, are immaculately produced. “When I got into the studio with Martin, I had what you might call a blueprint for “Pressure”, but it wasn’t what it ended up becoming,” Duncan says. “Things evolved a lot as we worked on it in the studio. We stripped the demo completely apart, and then developed each of the elements individually. I went in with a track, we took it back to basics, and with more equipment and skills this whole new record developed out of it.”

Duncan is full of praise for the role Williams played in the production process. “He brought a lot of experience and expertise,” he says. “Martin allowed me the freedom to take my game up to another level. It was the meeting of these worlds that helped the record evolve”. Duncan describes a series of studio sessions that involved a lot of experimentation, including layering up samples of bass notes from other BASSIC releases in an attempt to get a heavier sound. “We worked on the bassline a lot,” he says. “We just kept tweaking it to try and make it as dubby and deep as we could. We’d keep doing this until we ended up with a sound that we liked. It was all just a slow process of creating, tweaking, and creating more.”

The laborious process was worth the effort. Even now, 27 years on, the Pressure EP is arguably the greatest example of bleep in its purest form: industrial-fired future dub for the acid house generation.“I was quite sceptical to begin with,” Duncan admits. “Because the record took so long to make and finish, the scene was already beginning to change by the time it came out. Records were getting faster and faster. I did wonder whether the record was too late, or whether I’d missed my moment. In the end, I was wrong, because it did really well.”

While his record was becoming an underground anthem – both up north, and in the sets of London trendsetters Fabio and Grooverider – Duncan moved back into the shadows. While he continued to record demos at home, he would release no more 12” singles. He did, though, act as a producer for other artists. “Someone wise once said: ‘when you work for other people, your work ends up being watered down, and you can’t really be yourself’,” he sighs. “I found that to be quite true.” The good news is that fresh Ability II music could be appearing soon. Duncan says that he’s now putting the finishing touches to what would be his debut album. He hopes to start releasing new music from this summer onwards.

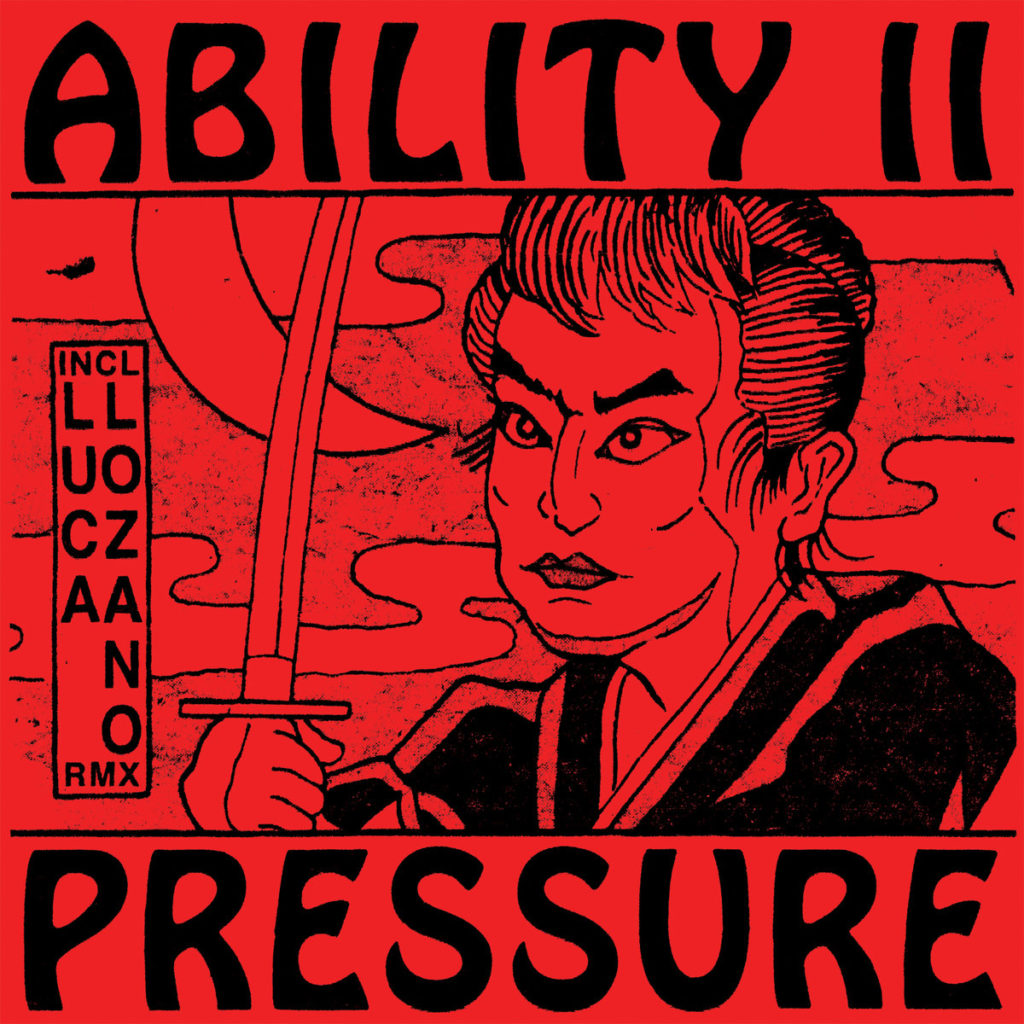

In the meantime, we can enjoy Major Problems’ lavishly produced reissue of his seminal record. The re-mastered original tracks are accompanied by a fresh remix from Luca Lozano – completed without any access to the long-lost original master tapes – and, if you grab a copy direct from the label, an insert sheet featuring David Duncan’s memories of making the track. It’s a fittingly good reissue of a timeless record. When I offer this assessment of Pressure, Duncan bristles with pride. “That was the idea,” he enthuses. “I wasn’t just making a record, I was making a piece of music that I wanted to last the test of time. Some people at the time were making records just to make records. For me, because I’d been making electronic music for quite a few years, I wanted there to be more artistry behind it. I think that’s why it’s so unique in its’ own way”.

Ability II’s ‘Pressure Dub’ is out now on Major Problems

Matt Anniss’s book on the history of bleep and bass and the dawn of UK dance music’s love affair with bass, Join The Future, will be published later in the year.