Tom Govan on the history and trail of drum machines in modern music

Intrepid rhymic explorer, DJ and fine wordsmith Tom Govan returns to Innate to furnish us with another in-depth article where he trawls through the history of the drum machines, and their incursion into popular music. Off the back of a very fine radio documentary he compiled, recorded and edited for Noods Radio back in October 2025, which we highly recommend listening to. Tom kindly agreed to create a written article to accompany the show in a long read format, for you to take in at your leisure between the beats.

Part 1 — The Early Years…

In the dim light coming from the daylight at the cave entrance a troglodyte man sits panting waiting for a predator to pass. To accompany his fearful breathing is the steady pulse of water dripping into a puddle on the cave floor; eventually as he calms the man finds the drip eventually synchronises with the thick beat of his own heart.

From the beginning, humans have lived in the midst of rhythm. The pulse of life has always surrounded us— woven into the fabric of nature, echoed in our footsteps, and felt in the quiet throb of our own bodies. These rhythms were once organic, spontaneous, and deeply personal.

Then came the machines. Modern man standing not in a cave but in the thrash of heavy machinery.

The industrial age introduced a new kind of rhythm: mechanical, relentless, and often deafening. The roar of engines, the hum of factories, and the click of automation began to shape our sonic environment. Machines became essential to our survival — and sometimes, our undoing.

Music, too, has always been a rhythmic expression of humanity. In its earliest forms, musical rhythm was crafted by hand — drums made from stretched skins, tapped out in communal dances. As music evolved, the drummer became the heartbeat of the band, the fulcrum around which melodies turned. But technology had other plans.

By the early 20th century, rhythm-making began to shift from human hands to electronic circuits. Drum machines emerged, offering precision, consistency, and a new aesthetic. For some, these machines were revolutionary — pragmatic tools that expanded musical possibilities. For others, they were soulless grids, lacking the nuance and imperfection that made rhythm feel vigorous, organic and animate.

This uneasy relationship between humans and drum machines is the focus of our exploration. How have we tried to humanize these devices? Can circuitry carry soul? And what stories lie behind the machines that shaped the sound of modern music?

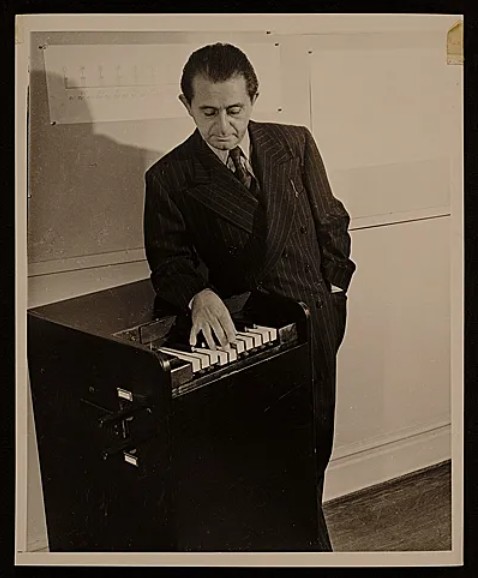

We begin with the Rhythmicon, a curious invention born from the mind of avant-garde composer Henry Cowell and built by the legendary Leon Theremin in 1932. Designed to produce complex cross-rhythms, the Rhythmicon was a marvel of its time — but far too esoteric for mass adoption. Cowell composed a few pieces with it before abandoning the project, and the Rhythmicon faded into obscurity.

Next came Bandito the Bongo Artist, a whimsical yet sophisticated rhythm device created by the enigmatic Raymond Scott in the early 1960s. Intended to mimic the flair of hand percussion, Bandito was never mass-produced, but its legacy lingered in Scott’s archives until rediscovered decades later.

More practical was Harry Chamberlin’s Rhythmate, developed in 1949. Using magnetic tape to play back real drum sounds, the Rhythmate offered a more direct imitation of a live drummer. Though it never reached commercial success, it laid the groundwork for future sampling technologies. One unit even found its way into the hands of lo-fi legend Phil Elverum, echoing through the hazy textures of his Microphones recordings.

From these early experiments, the drum machine began to evolve — slowly, then rapidly. In the next part of this article, we’ll explore the rise of Ace Tone, the pioneering company founded by Ikutaro Kakehashi, and how its innovations helped shape the future of rhythm in popular music.

Illness nearly defeated the young Ikutaro Kakehashi. Struck down with tuberculosis in the early 50s, Kakehashi recovered sufficiently to open his own electrical repair shop in Osaka. Initially specialising in radio repair the industrious young engineer branched out to start building electronic organs from scratch. By 1960 Kakehashi had developed enough expertise to justify starting his own company, Ace Electronic Industries Inc. and 1964, Kakehashi had begun to dip his toe in the world of electronic rhythm. In that year he created a prototype of the world’s first fully transistorized percussion instrument that lacked automation. Instead of offering preset rhythms, it produced individual percussion sounds when specific buttons were pressed. This design made it impractical for organists, who were the primary target audience at the time. The instrument was introduced at the Summer NAMM Show in 1964, but it never reached commercial production. Nevertheless, it served as an important stepping stone for future innovations.

In 1967, to better satisfy the growing demand for an automatic rhythm machine, Kakehashi developed a circuit known as a diode matrix. This system generated rows of pulses that controlled the timing and placement of each instrument sound within the machine. The innovation led to the creation of the FR-1 rhythm machine, which featured 16 preset patterns and four buttons for manually triggering individual voices such as cymbal, claves, cowbell, and bass drum. Users could combine patterns by pressing multiple rhythm buttons at once, unlocking over 100 possible rhythm variations. The design proved so successful that the Hammond Organ Company later integrated FR-1 presets into its newest organ models.

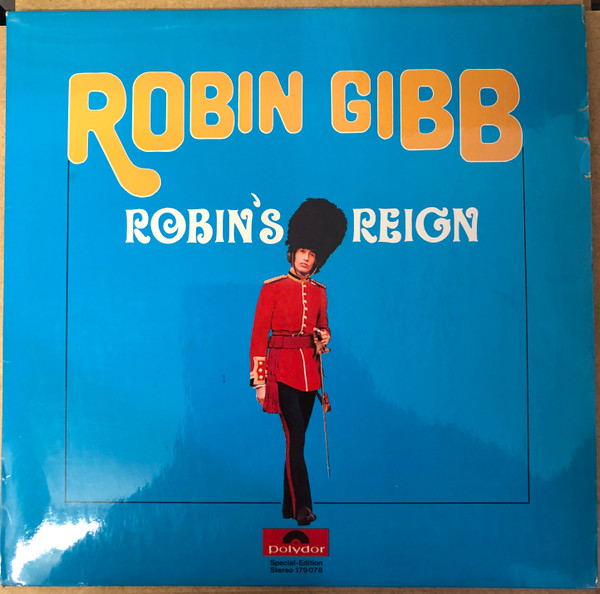

Kakehashi’s Ace Tone units were the first drum machines to be used on commercially available recordings. Indeed one of the early adopters was not, as you may have thought, some austere technocratic studio boffin but instead a disgruntled Bee Gee. Robin Gibb had found fame in the mid 60s with his brothers Maurice and Barry but by the late 60s all was not well in the world of Gibb. A sibling rivalry had developed between the lion haired falsetto voiced figure of brother Barry and the taciturn yet soulful Robin, both were vying for lead singer and by 1969 the internal differences led Robin to leave the his brothers and work on solo material, and in so doing Robin made a pioneering drum machine record.

Recorded in a hurry one can assume that Gibbs decision to liberally use an Ace Tone FR-1 drum machine within his first solo record, Robin’s Reign, was predicated on expediency rather than wilful experimentalism. There is very little in the way of interview material from Robin or the producers he worked with on the album that expounds on the reason to rely on mechanised rhythm but superfans have speculated that the decision to use a drum machine revolved around Robin’s desire to work on vocal tracks alone on with just the metronomic accompaniment of the FR-1 for company. The orchestral overdubs were added later by producer Kenny Clayton and the resultant mix heard on the final record, of the disembodied drum sounds, Gibb’s heartfelt singing and the rich orchestral chamber pop instrumentation, is both stark and remarkable.

Gibb was not alone as being an artist more comfortable in the presence of just a drum machine. Indeed if one man can be credited with becoming the first public demonstration of man’s union with drum machine it has to be Sylvester ‘Sly Stone’ Stewart. In the late 60s, Stone took a shine to a Maestro Rhythm King lying around in a studio and started to compose with it as a time keeping device having become estranged from his human drummer, Greg Errico. As an early adopter of a drum machine Sly seemed to understand the potential for the instrument to become part of a home studio environment where entire compositions could be created without the need for live ensemble playing. The Family Stone started to take more of a back seat as Sly became increasingly reclusive and drug dependent. Live gigging faded in favour of tinkering with his the Rhythm King, now christened the ‘funk box’ by Stone, in his bedroom studio whilst alledgedly being completely shermed out of his nut.

6IX — I’m Just Like You

In 1970, Sly put his funk box to use on a track for his short lived music label Stone Flower. Although credited to the band 6IX, the track ‘I’m Just Like You’, is mostly of Stone’s invention; the gooey funk side features the Maestro Rhythm King riding high in the mix alongside Stone’s lazy bass ooze, some harmonica from band member Marvin Braxton and singing from Chuck Higgins. This would prove to be a portent for what Stone was cooking up for his next Family Stone record. Released in 1971 ‘There’s A Riot Goin’ On’ displayed all of the woozy and brooding paranoia refracted from Stone’s drug addled mind with every track having the smeared patina of a hundred overdubs. But notably it was Stone’s use of his funk box that made the album a pioneering piece within the history of recorded drum machines. Rather than deploying the presets straight into the tracks, Stone became adept at overdubbing in individual hits to merge with sounds from a drum kit, or would experiment with phrasing, starting the presets at irregular places in the musical bar.

J.J. Cale — Call Me The Breeze

A year after Family Affair hit the charts, bluesman J.J Cale introduced the Ace Tone Rhythm Ace into his own work on the 1972 track Call Me the Breeze. While Sly Stone had used a drum machine as a creative tool —s haping grooves and building compositions around its mechanical pulse — Cale’s motivation was far more pragmatic. At the time, he was operating on a shoestring budget, unable to afford the luxury of hiring session drummers. The Rhythm Ace became his dependable stand-in, providing a steady beat without the cost or scheduling headaches of live players. It was a choice that was reflective of not only the financial exigencies of many independent musicians in the early ’70s but also underscored how drum machines were beginning to shift from novelty gadgets to practical instruments.

Can — Spoon

Before Kraftwerk fully embarked on their journey toward the ideal of the “Man-Machine,” a handful of German experimental rock pioneers were already flirting with the creative possibilities of drum machines. Among these early adopters were the legendary Can, a band whose rhythmic foundation was built on the extraordinary precision of drummer Jaki Liebezeit. Liebezeit’s playing was so mechanically exact that it rivaled any electronic rhythm generator, making the idea of Can incorporating a drum machine seem almost paradoxical. Yet, on their 1972 track “Spoon,” the band did just that. A Farfisa drum machine was woven into the fabric of the song, not as a replacement but as a counterpoint to Liebezeit’s hypnotic groove. Guitarist Michael Karoli unleashed bursts of percussive patterns from the Farfisa, creating a layered rhythmic dialogue that pushed against the main drum track. This interplay between human and machine hinted at the future of electronic music while remaining firmly rooted in Can’s organic, improvisational ethos — a fascinating moment where technology served as an extension rather than a substitute for human creativity.

Arthur Brown’s Kingdom Come — Spirit of Joy

For Arthur Brown’s Kingdom Come, the early 70s proved to be an epiphany in deciding who should occupy the drummer’s seat. After enduring three problematic human drummers — one of whom famously stole their tour van — the band opted for a radical solution: replacing flesh and blood with circuitry. Enter the Bentley Rhythm Ace, a drum machine from Mr Kakehashi’s Ace Tone stable, which took over percussion duties for the entirety of Kingdom Come’s third and final album in 1973. The result was a sound that felt both futuristic and defiantly unconventional.

Timmy Thomas — The Coldest Days Of My Life

This bold move wasn’t an isolated experiment by eccentric rockers. Around the same time, Timmy Thomas was charting his own minimalist course in soul music. Inspired by Sly Stone’s earlier innovations, Thomas recorded an entire album using nothing more than his Lowrey organ and its built-in drum machine. The lead single, the haunting anti-war anthem Why Can’t We Live Together, became a classic, but for me, the standout is the tender, autumnal ballad The Coldest Days of My Life. It’s a masterclass in how simplicity can amplify emotional depth.

The Upsetters — Chim Cherie

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic in Jamaica, drum machines were quietly rewriting the rules of rhythm. In 1973, the Eko Computerhythm — the first programmable drum machine ever made — found its way into the hands of Aston “Family Man” Barrett, legendary bassist for The Wailers. While working with Lee “Scratch” Perry, Barrett programmed a pattern that became the backbone of the Chim Cherie riddim, first released by The Upsetters that same year. This marked the first known use of a drum machine in Jamaican music and foreshadowed the digital dancehall revolution that would erupt in the mid-’80s.

Part 2 — And The Beat Goes On

As the 1970s progressed, the presence of drum machines in popular and experimental music grew steadily, moving from being an occasional exotic occurrence to a defining feature of certain recordings. What began as a curiosity on the fringes soon became a tool embraced by artists across genres. By the mid-decade, these devices were no longer confined to electronic pioneers—they were infiltrating rock, jazz, and avant-garde circles alike.

Ron Wood — Crotch Music

One of the earliest high-profile adopters was Ronnie Wood, who incorporated a drum machine on his first solo album in 1974. The track in question bore the cheekily provocative title “Crotch Music”, a piece that showcased how rhythm boxes could add a quirky, mechanical pulse to otherwise organic rock arrangements. If even a Rolling Stone, the bastions of fleshy rock, were embracing computer drummers then maybe there was an extended life for these strange boxes.

Meanwhile, in the world of jazz fusion, Miles Davis — never one to shy away from innovation — allowed drum machines to punctuate and embellish his mid-1970s work. On the 1975 track “Turn of the Century,” percussionist James Mtume deployed a Yamaha EM-90 rhythm device, slicing through the dense funk-rock textures with its insistent electronic patterns. This integration of machine-driven rhythm into Davis’s sprawling sonic landscapes hinted at a future where jazz and electronics would intertwine more deeply in the hands of Herbie Hancock and others.

Brian Eno — Burning Airlines Give You So Much More

At the same time, the art-rock sphere was undergoing its own transformation. Brian Eno, freshly departed from Roxy Music, embraced drum machines extensively on his early solo albums. On his 1974 sophomore effort, Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) the opening track “Burning Airlines Give You So Much More” begins with the unmistakable tick of a Bentley Rhythm Ace, laying down a rigid yet hypnotic rhythmic bed. For Eno, these devices were not mere substitutes for drummers—they were compositional tools, shaping the very architecture of his songs and reinforcing his vision of music as a studio-based art form.

Brian Eno — Sombre Reptiles

By 1975, Brian Eno had begun pushing drum machines far beyond their intended function. On his landmark album Another Green World, he subjected these devices to heavy processing and studio manipulation, transforming their rigid pulses into abstract rhythmic contours. Tracks like “Sombre Reptiles” exemplify this approach — where the machine’s mechanical regularity becomes a textural element rather than a simple timekeeper, dissolving into Eno’s dreamlike sonic landscapes.

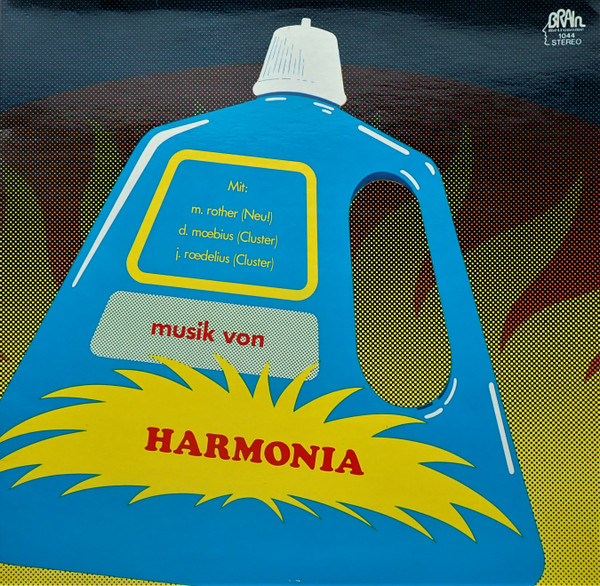

Eno’s fascination with drum machines didn’t emerge in isolation. His creative use of these tools was deeply influenced by the experimental ethos of German rock musicians, many of whom had been integrating machine-generated rhythms since the early 1970s. Groups like Harmonia — a collaboration between Dieter Moebius ,Joachim Roedelius, and Michael Rother — were central to this movement. Their track “Watussi” is a perfect example: a hypnotic blend of electronic pulses and organic instrumentation that blurred the line between human and machine. Eno was so captivated by Harmonia’s work that he famously declared them “the most important band in the world” at the time.

Harmonia — Watussi

This admiration soon led to direct collaboration. In September 1976, Eno traveled to Harmonia’s rural studio in Forst, where they recorded an album together under the name Harmonia 76. The sessions continued the exploration of mechanized rhythm, with tracks like “Vamos Campaneros” weaving drum machines into shimmering layers of guitar and synthesizer. These recordings not only deepened Eno’s commitment to electronic rhythm but also laid the groundwork for his later ambient experiments and his influential production work with artists like David Bowie and Talking Heads.

Harmonia 76 — Vamos Companeros

What began as simple rhythm devices had, in Eno’s hands, become instruments of abstraction— tools for sculpting time and texture rather than merely keeping beat. His dialogue with German innovators marked a turning point in the evolution of electronic music, setting the stage for the ambient and post-punk revolutions that would follow.

Kraftwerk on BBC’s Tomorrow’s World 1975

Few bands can claim to have created such an iconic showcase for electronic rhythm as Kraftwerk. Emerging from the same experimental German milieu as Harmonia, Kraftwerk had, by the mid-1970s, resolved to abandon traditional instrumentation and commit fully to the pursuit of machine-made music. Their approach involved heavily modified Farfisa and Vox rhythm units, which became central to their futuristic sound. This vision was so striking that it earned them a feature on BBC’s Tomorrow’s World in 1974, where they demonstrated their electronic pop innovations with two members tapping out beats on altered drum machines during a performance of “Autobahn.” The appearance polarized critics—one NME journalist sneered that they sounded “so detached… the kind of guys who could blow up the planet just to hear the noise it made.” Yet, for every detractor, there were countless admirers who saw Kraftwerk as prophets of a new musical age.

While Kraftwerk were redefining European electronic music, another figure was preparing to revolutionize the dance floor: Giorgio Moroder. Working with American vocalist Donna Summer, Moroder and his team faced a practical challenge—live drummers struggled to maintain the unwavering tempo required for extended disco tracks. The solution came in the form of a Korg MiniPops drum machine, which anchored their productions with mechanical precision. On tracks like “Love to Love You Baby” and, most famously, “I Feel Love,” Moroder fused machine rhythms with acoustic kick drums to create a hypnotic pulse that captured the public imagination. “I Feel Love” was dominant in the clubs and signaled the dawn of electronic dance music, proving that drum machines could be at once sensual and futuristic.

If disco brought drum machines into the mainstream, the underground found its own drum machine champions in Suicide, the New York duo of Alan Vega and Martin Rev. Their story of drum machine acquisition is as strangely compelling as their sound: Rev acquired a Seeburg rhythm unit from a grieving couple whose poet daughter had used it to accompany her readings before taking her own life. This macabre provenance only deepened the aura surrounding Suicide’s music. On their harrowing 1977 single “Frankie Teardrop,” Vega’s bleak, violent lyrics ride atop the relentless pulse of the Seeburg, creating a track that feels like a descent into urban nightmare. It was a radical gesture; stripping rock down to voice, electronics, and machine rhythm.

By the time “Frankie Teardrop” emerged, punk was in full swing, and one might assume its fans would embrace the anti-establishment symbolism of a drum machine. Not so. When Suicide supported The Clash, they were met with hostility—missiles and abuse hurled at the stage—simply for daring to perform without a drummer or guitars. This reaction exposed punk’s conservatism: despite its rhetoric of rebellion, the genre clung to the same old blues-rock palette of real drums, guitars, and bass. Yet, beyond the chaos, Suicide’s audacity planted seeds in the minds of future innovators.

Those seeds sprouted in the north of England, where groups like Throbbing Gristle, Cabaret Voltaire, and The Human League embraced drum machines as instruments of liberation from the dominance of the blues rock tradition. These acts forged a new sonic frontier — proto-industrial, abrasive, and defiantly modern. Throbbing Gristle’s Chris Carter twisted the preset rhythms of a Roland CR-78 into something sinister on “Hot on the Heels of Love.” Cabaret Voltaire subjected the same machine to effects treatments on the minimalist churn of “Talkover”. Meanwhile, early Human League paid homage to sci-fi writer J.G. Ballard on “4JG,” deploying the rhythms of a Korg System 100 to craft a stark, dystopian soundscape. These experiments were resolutely ideological, rejecting rock orthodoxy and embracing technology as a creative force.

From Kraftwerk’s pristine Autobahn to Suicide’s grim urban pulse, from Moroder’s disco futurism to the industrial rumblings of Sheffield, the drum machine’s journey through the 1970s was nothing short of revolutionary. What began as a humble rhythm box became a catalyst for cultural transformation, reshaping not only how music sounded but what it meant in an age increasingly defined by machines.

Hall & Oates — I Can’t Go for That (No Can Do)

As the 1980s dawned, drum machines were now part of the furniture in most professional studios.. One of the key players in this transition was the Roland CR-78, the brainchild of Ikutaro Kakehashi, who had previously founded Ace Tone before establishing Roland. By the early ’80s, the CR-78 had earned a reputation as a respected—if not mass-market—drum machine. Its modest programmability and versatility meant it could be used for more than just organ accompaniment or demo tracks. Pop artists quickly embraced its distinctive sound, and it became a subtle but defining presence on records of the era. Two prime examples are the elegant New Romantic anthem “Fade to Grey” by Visage and the unforgettable intro to Hall & Oates’ 1981 classic “I Can’t Go For That.”

Spontaneous Overthrow — All About Money

Back on the experimental fringes, drum machines continued to serve as lifelines for DIY musicians operating on shoestring budgets. In the UK, Martin Newell’s Cleaners From Venus project leaned heavily on the Soundmaster SR-88, crafting lo-fi pop gems with its rigid pulses. Across the Atlantic, equally eccentric experiments were unfolding. One standout comes from Spontaneous Overthrow, whose track “All About the Money” — unearthed on Dante Carfagna’s essential compilation Personal Space — pairs an unidentified rhythm box with woozy, homespun funk. By the ’80s, drum machines had become indispensable not only for bold new steps in the mainstream but also as essential band members for cash-strapped visionaries.

While these machines were democratizing music-making, a quantum leap was about to occur. Enter Roger Linn, a seasoned musician and engineer who founded Linn Electronics. His first creation, the LM-1, changed everything. Unlike previous drum machines, which relied on synthesized or preset tones, the LM-1 used digitally sampled recordings of real drums, allowing musicians to program authentic, studio-quality beats with machine precision. For the first time, human drummers faced a genuine rival — a programmable “robot” capable of infinite repetition without fatigue. The LM-1 quickly became ubiquitous throughout the decade. Early adopters included Linn’s mentor Leon Russell, who used a prototype extensively on his 1979 album Life and Love. Soon, the LM-1 was powering hits like The Human League’s “Don’t You Want Me” (1981), where its rock-solid beat helped define synth-pop’s polished aesthetic. Even film embraced its futuristic sound — John Carpenter deployed the LM-1 on his cult soundtrack for Escape from New York. And then there was Prince, perhaps the machine’s most iconic champion, who bent its capabilities to his will on tracks like “Private Joy” from Controversy. For Prince, the LM-1 wasn’t just a tool — it was an instrument of seduction and innovation.

Mikel Rouse — Quorum

The LinnDrum’s cultural impact was so profound that it inspired entire conceptual projects. In 1984, Mikel Rouse dedicated an entire LP (Quorum) to intricately programmed LinnDrum patterns, challenging the notion that drum machines were inherently “cold” or “mechanical.” Rouse argued that such criticisms stemmed from conventional usage, and his work anticipated the experimental electronica of the 1990s, proving that drum machines could be expressive, even poetic.

Ryuichi Sakamoto — Riot In Lagos

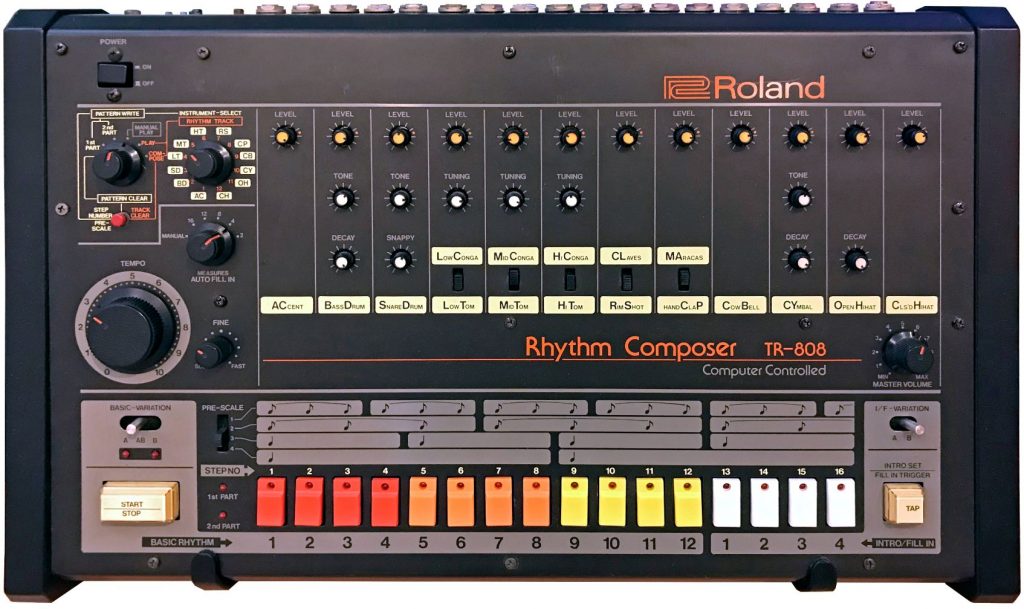

Meanwhile, Roland was preparing its own revolution. Building on the cult success of the CR-78, Kakehashi’s team developed the TR-808, a machine designed to compete with the LinnDrum but radically different in concept. Instead of sampled acoustic drums, the 808 generated sounds through analog synthesis, producing a palette of tones that were at once artificial and deeply compelling. Initially, the 808 seemed destined for obscurity, but its unique timbres soon became the backbone of entire genres. Before its official release, the unit was tested by Yellow Magic Orchestra, and member Ryuichi Sakamoto immortalized it on his solo track “Riot in Lagos”— a piece now regarded as a blueprint for electro. Around the same time, Suzanne Ciani, a pioneering female composer in electronic music, embraced the 808 for her 1982 LP Seven Waves, using its rhythms to underpin lush ambient soundscapes. For Ciani, the machine offered creative freedom in a space less burdened by the gendered hierarchies of traditional music scenes.

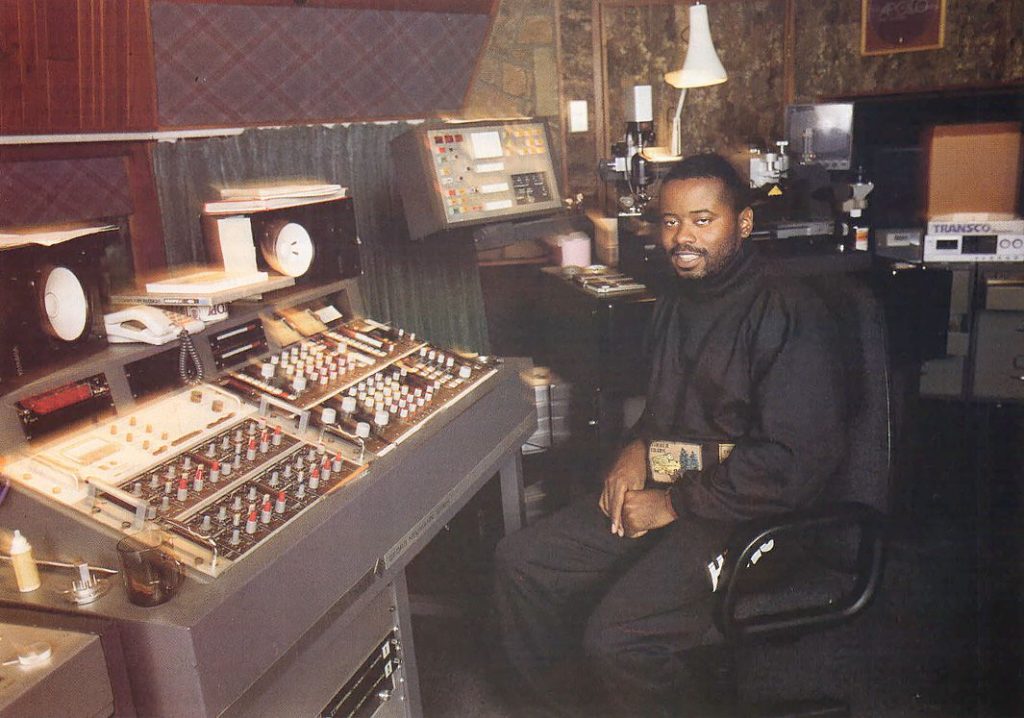

The 808’s journey into the mainstream was cemented by Marvin Gaye, who, exiled in Belgium and cut off from the U.S. studio system, turned to the drum machine as a compositional partner. The result was “Sexual Healing” (1981), a global hit that showcased the crisp, sensual punch of the 808 and redefined the possibilities of soul music. Then came Planet Rock (1982), produced by Arthur Baker and John Robie for Afrika Bambaataa & the Soulsonic Force. By splicing Kraftwerk samples with 808 beats, they created one of electro’s foundational tracks — a record that not only revolutionized hip-hop but enshrined the 808 as a cultural icon. In the wake of Planet Rock, legions of producers embraced the machine, none more famously than Greg Broussard aka The Egyptian Lover, who built his slinky, mythic brand of electro around the 808’s thunderous kicks and sizzling snares.

By the mid-1980s, drum machines were no longer novelties — they were shaping entire genres, from synth-pop and electro to hip-hop and experimental electronica. What began as humble rhythm boxes had evolved into instruments of cultural transformation, redefining the sound of modern music and laying the foundation for the digital age.

New Order — Blue Monday

By 1982, the drum machine had become more than a studio tool—it was shaping entire genres. One of the most influential examples came from Klein & M.B.O. Their track “Dirty Talk,” produced by Mario Boncaldo and Tony Carrasco, fused the sleek, synthetic sheen of Italo disco with the muscular rhythmic grid of the Roland TR-808. The result was an underground sensation that rippled across dance floors and into the DNA of emerging electronic styles. Its minimalist groove would inspire New Order’s “Blue Monday”, albeit with Blue Monday using the Oberheim DMX, and it would compel Chicago house producers to replicate its rhythmic architecture, laying the foundation for a new era of dance music.

Ironically, Roland soon discontinued the 808, deeming it a commercial failure. Units were sold off at discount prices, and in Chicago, several fell into the hands of a group of non-musicians eager to craft post-disco tracks using machines. From this unlikely scenario, Chicago house was born. Fed by the musical diet of DJ Frankie Knuckles at the Warehouse nightclub, producers stepped forward to fill the void as disco’s supply dwindled. The 808 became pivotal in this low-budget production world, powering early house records by Jesse Saunders, Marshall Jefferson, Steve “Silk” Hurley, and Chip-E. Their stripped-down, repetitive grooves defined a new sound — minimalist, hypnotic, and tailor-made for the dance floor.

Meanwhile, in Detroit, another Roland machine was rewriting the rules. The TR-909 lacked the brute force of the 808 but offered cleaner, more precise hits that suited the futuristic ambitions of Detroit’s techno pioneers. In the hands of producers like Juan Atkins, the 909 became the cornerstone of a colder, sleeker, and more aggressive strain of electronic dance music. Tracks such as Model 500’s “Electric Entourage”— with its Kraftwerk-inspired motifs — signaled a new chapter: techno as a vision of tomorrow with the electronic pulse of the drum machine as a propulsive force to disrupt the rock drummer hegemony.

“The music is not for everybody. It’s for certain people that want a little twist. Some people are perfectly content with the everyday pop – they don’t have an open enough mind to consider something new. Those aren’t the people I’m playing for; they’ll come around eventually, ‘cos they’re basically followers. When they’re told this is what’s happening, they’ll go along with it.” Juan Atkins – (‘Future Shock’ Article from Music Technology, December 1988).

Juan Atkins’ prophecy turned reality. By the turn of the millennium, the drum machine had become part of the fabric of every professional studio, with dedicated programmers ensuring flawless rhythm tracks. Yet its hardware form was under threat. The rise of Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs) like Logic and Pro Tools allowed drum programming to move “in the box,” eliminating the need for bulky machines. Still, the drum machine never truly disappeared. As production shifted to software, a fetishism for classic hardware emerged. Discontinued units like the 808 and 909 began commanding eye-watering prices on the second-hand market, and boutique manufacturers stepped in with clones. Even Roland returned to its roots, announcing the TR-1000, its first all-analog drum machine in 40 years.

This resurgence reflected a deeper truth: musicians craved the tactile immediacy of hardware. As synth pioneer Robert Margouleff observed when talking about the role of hardware in the studio, “It’s something primal in us, the need to beat on something. Put us in a situation where rhythm is required and humans will use whatever is at hand to create a rhythm. We don’t need a mouse and a screen”.

Jeff Mills Exhibitionist 2 Mix 3

A small and sharp faced figure clad in smart black clothing is crouched over the facia of a large plastic box resembling some sort of oversized fax machine. It is in fact a TR-909 drum machine and the crouching player is techno wizard Jeff Mills, a man who far beyond anyone else has synergised himself with the drum machine. For the next ten minutes of the ‘Exhibisionist’ video Mills crouches in a state of complete concentration communing with the 909 with all the ease and grace of a classical conductor. In ten minutes Mills summons a delirious cascade of rhythms from the 909; from stripped piledriver segments of kick drums to densely layered avalanches of claps, snares and hats threatening to engulf you.

As Mills so joyously demonstrates the (in) human story of drum machines is one in which the drum machine has moved from novelty to a full fledged instrument. It’s a story stared by some ingenious inventors in the early 20th century who envisioned mechanical rhythms as part of the arsenal of the one man band. Over time and given commercial development and manufacture the drum machine evolved from being a gimmicky box at the side of an organist to becoming a cherished workhorse within the commercial studio. As technology evolved the creative potential of the drum machine became fully expanded to allow for dynamic drum programming that surpasses what even the most octopus-like of human drummers could muster. But despite the warnings from the rock bores, the drum machine has not replaced the human drummer, it’s just given us a lot of great music.

Further reading and viewing

https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/dancing-to-the-drum-machine-9781501367298

https://danleroysbonusbeats.substack.com/p/rhythms-remembered-mobys-drum-machine