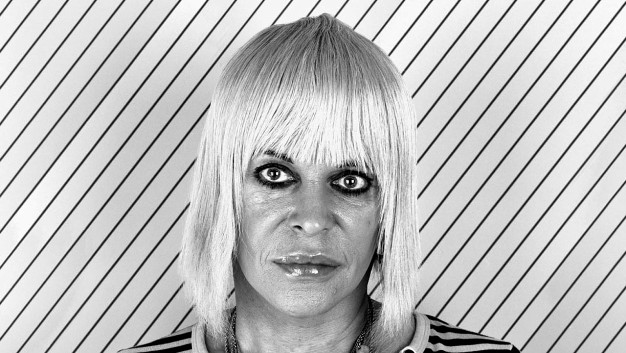

Jonah Sharp is probably best known as being one half of live techno act Reagenz, alongside fellow electronic music veteran David ‘Move D’ Moufang

For those of us with long memories, Jonah Sharp will always be remembered as Spacetime Continuum. Under the alias, he produced some of the greatest ambient techno releases of the 1990s, developing a style that sat somewhere between the head-in-the-clouds dreaminess of Pete Namlook (an artist he worked with in the mid ‘90s), the ‘intelligent techno’ of B12 and The Black Dog, and the emotion-rich deep house of Larry Heard.

Having moved to London at the tail end of the ‘80s, Edinburgh-born Sharp quickly became involved with the nascent rave and chill-out scenes. By the early ‘90s he’d relocated to San Francisco, and played a huge role in the fast-growing Bay Area electronic music scene. A string of fine singles and albums followed, as well as a clutch of notable collaborations (Bill Laswell, Mixmaster Morris, Tetsoi Inoue, and, most famously, legendary psychedelic thinker Terrence McKenna).

In recent years Sharp’s career has been given a boost by the rebirth of Reagenz, a project that began two decades ago, and his collaboration with Rong Music boss DJ Spun under the Loose Control Band alias. Last autumn, Matt Anniss decided to drop Jonah a line, to see if he would like to make a contribution to a history of ‘90s ambient house and “chill out” he was writing for Red Bull Music Academy. Luckily, he gladly agreed, and the pair spent a couple of hours chatting on Skype about his role in the ambient revolution, his career and, of course, the future of Reagenz.

What follows is an edited transcript of Matt & Jonah’s conversation, which has been given for us to publish in full.

JONAH SHARP (JS): As you get older, you realise that the people in your generation are all weirdly connected. I keep finding that I was at the same parties as people I meet 20 years later. I went to Sunrise in ’89, and now I bump into people who say that they were there.

MATT ANNISS (MA): Is that like the rave equivalent of the Sex Pistols gig in Manchester that everyone says they were at?

JS: It kind of is! There were probably about 20,000 people there, and roughly three-quarters of them had never heard that music in that kind of setting. I really had a sense that I was at a huge event, and that this scene is only going to get bigger. It was a complete accident that I went there. Somebody said: ‘there’s this thing going on in a field, let’s go’!

MA: Had you started making electronic music at that point, or were you in your acid jazz drummer phase?

JS: I was kind of in both worlds. I was a young lad living in London, playing drums with different bands. I’d been in a succession of bands – punk bands, acid jazz bands – throughout the ’80s. The bands that I was in, we were experimenting with electronics all the time. The point of reference for us was Cabaret Voltaire. I was at art school in Newcastle, and used to nip down to Sheffield to go to the Leadmill to see the Cabs play. Seeing Cabaret Voltaire gave me inspiration and direction. When rave came around, it seemed to join everything together. Although I never became a total raver, I was always interested in the fringe aspects that became connected to rave. I wasn’t going to start running around in a top hat!

MA: When was it that you first met Mixmaster Morris?

JS: In 1988, I think, when he was opening for The Shamen, playing completely live with drum machines and a sampler. I thought: ‘holy shit!’ Somebody doing it solo like that was unheard of. I just remember it being completely chaotic and not making much sense, but it was cool because of that. He had a TR-606 drum machine, clattering away. It totally inspired me, though. I thought it was a great concept – live drum machines!

MA: Did you introduce yourself to him that night?

JS: Yes. I wandered up to him and said ‘that was awesome, I loved your show’. It turned out he lived up the road from me in Camberwell. He was very welcoming – he just said: ‘come over, check out some records’. It was an eye-opener what Morris was listening to then. He had a white label of Aphex Twin’s Analogue Bubblebath, and introduced me to The Black Dog as well.

MA: Morris was involved with the Spacetime events, which often get cited as some of the earliest chill-out events in London. When were the first parties?

JS: Around ’89-90, probably 1990. My art school buddy Richard [Sharp] was running a clothing company called Spacetime. We’d been working together musically and using that name. Mr C was a friend of Richard’s, and he was one of the resident DJs at the Spacetime parties, alongside Mixmaster Morris and myself. The parties were pretty small to begin with. The first one, there was only about 50 people there. It was so much fun, because it was in such a cool space in Limehouse in East London. We put these parties together every couple of months, until the last one, which was completely insane. Everyone who was anyone showed up. Bjork was there. I’ve no idea how she found out about it!

MA: Were they full on rave events, or was there an ambient element?

JS: There was definitely an ambient element. They started out as chill-out parties, because Morris was our friend. There was this idea that we were stretching out towards the left field, and championing things like The Black Dog. I was really aware that there was this distinctively British reaction to certain American mid-west music that was taking this new form. It was kind of chill-out, but it wasn’t new age. It was sort of rave-related. It had more of Detroit influence than, say, the Tangerine Dream influences that you got in early Orb records. I was really into Larry Heard and that kind of jazz-influenced house sound. That was definitely a related element.

MA: What people in the press – particularly Morris in his NME column – called ‘intelligent techno’?

JS: There was that kind of aspect to it, when you’re thinking about the fact that we pushed artists such as B12 and Autechre. I guess there was that aesthetic, and ambient records, but we never got too noodly. I remember there was this ‘ambient house’ compilation going round, which I really liked. It had things like the Derrick May mix of Sueno Latino on it. That kind of sound was closer to what we were doing.

MA: How would the party develop over the course of the night?

JS: Richard and Mia, who was working at Spacetime, would put up hologram fabric, and dress up the walls. It was like a little art installation. It would start off very much like a listening room, and would end up crazy – especially the last one, when people were jumping around on the roof. That’s when the cops turned up! My perception of what was going on by that point in 1991, was that the beats were getting faster and faster.

MA: That’s certainly true. Earlier this year I wrote a piece about techno in Rome, which took the British sound and made it even more intense.

JS: At that point, people were realising the possibilities of where they could go creatively with the blueprint of dance music. That’s how the ambient or chill out room came about. You had to have it, because the music was so fucking intense that you had to go and chill out somewhere. My first gigs at parties in England were in the chill out rooms. I was “the chill out guy”, along with Morris, in “the other room”. It was where we could play our Carl Craig and Black Dog records, as well. I also used to play stuff by people like the Moody Boys.

MA: That ‘Journeys Into Dubland’ EP that Tony Thorpe did with Jimmy Cauty, under the Moody Boys name, was around that time, wasn’t it? That’s such a good record.

JS: I was really into all that stuff. You’d only hear it in London, because it really could only have come out of London. It was a very interesting time, and I kind of wish I’d stuck around longer. I got the opportunity to come to San Francisco, and I brought that vibe to the city. When I arrived, I was the only person doing it. There weren’t that many people here from England, and there was really no rave scene at all when I got here. That’s why it seemed a good place to set up camp.

MA: Was the acid counter-culture that San Francisco’s renowned for still going on at the time?

JS: When I got here, there was this huge influx of Brits, and Irish, and French – a European invasion. It was fairly small in the grand scheme of things – between 50 and a hundred people – but all these people started doing parties. It was like we were importing rave culture into America. The first month I was here, I got a residency because I was a British DJ. That was all it was! He’s from London… he’s massive [laughs].

MA: It sounds like you really hit the ground running.

JS: Strangely, I met Genesis P Orridge the month I got here. He moved here at almost the same time, and I ended up doing a load of shows with him. The first shows I did as Spacetime Continuum were opening up for Psychic TV. There’s this whole San Francisco culture of industrial psychedelia. Genesis really fit in – he adopted this rave, or dance music sound. I actually got asked to join Psychic TV, but I’d just made my first record for Reflective, my label, and wanted to do my own thing.

MA: Did the Terrence McKenna collaboration, Alien Dreamtime, come about quite soon after you moved to San Francisco?

JS: It all came about through a visual artist who knew Terrence. He said he wanted to do an event with Terrence speaking, and video, and maybe music. I suggested doing it as a conceptual rave, with Terrence as part of the show. So I met Terrence, and he was really open to doing something. He’d already done ‘Re:Evolution’ with The Shamen the previous year, but he’d never done anything that involved presenting his ideas in a more focused musical setting. He gave me a list of about six subjects that he wanted to talk about – the archaic revival, DMT, and so on. The idea was six sections, and I created music to go with his different ideas.

MA: Did you always think it would work as well as it did?

JS: I had no idea how it was going to turn out – we didn’t rehearse it, of course, we just did it. Beforehand, I sent him a cassette tape of my musical ideas for it and he was really into it. What was on that tape was really different to how it ended up, of course. That was the kind of thing that would have to happen in San Francisco – for many people in the Bay Area, it was an ‘I was there’ moment.”

MA: Listening to it again, it is very psychedelic and definitely ambient in ethos. I know there are beats and acid lines, but ambient at the time was quite a broad church. It didn’t have to be beat-less. It was more a sensibility I guess.

JS: What ended up on the [Alien Dreamtime] album was about half the show. Terrence came on three times. All of those bits are in tact on the record. Then there were the bits in between, where I would go off on another tangent. It was a two and a half hour show, so it was a lot of work. Those bits in between I used the 909 a lot, and it was full-on acid.

MA: The idea of the psychedelic experience through the intensity of the drums and the acid lines…

JS: Yeah, that kind of shamanic intensity to the drums. There were all these hippies there doing tree dancing and all sorts. The whole idea was to ensure that it wasn’t just repetitive intensity all night, and breaking it up somehow with ambient interludes. It made a lot of sense. I’d love to do something like that again, with that spoken word element.

MA: Terrence was in many ways the perfect person to do that. His voice was very evocative, because it didn’t sound like anyone else.

JS: He was a good showman. He had that Irish storyteller’s skill. He was really passionate about his ideas and his philosophies. He managed to deliver everything really well. It was astounding, really. I actually went to Los Angeles and played with Psychic TV, and Timothy Leary was talking at this rave in downtown L.A. It was kind of the same thing, but they had a DJ playing underneath. It didn’t really come across as well, it was more like the poetry room, with Tim Leary rambling on. It was really cool, because it was Timothy Leary, but most of the people there didn’t know who he was.

MA: Did you get a chance to talk to Timothy?

JS: Yes – I got to hang out with him. He talked to me about “this Internet thing” that was going to get “really big and change everyone’s lives”. I remember we were sat in his house up in the Hollywood Hills before the show. He was pointing at L.A and telling me that everyone was going to be connected. I remember thinking ‘wow, this Internet thing… what the hell is that’ [laughs]

MA: I also wanted to chat to you about Seabiscuit, which came out in 1994, and is a classic ambient album in my opinion.

JS: Back then my studio set-up was so rudimentary. I didn’t have a multi-track capability. I used to have to do everything live. That whole album, every track was done in three or four takes to work it out, then press record. I recorded it as a two-track. If it didn’t sound right, I’d have to do it again. I didn’t even have any way of editing it. It took six months of intense jamming and capturing the sound of the studio.

MA: A lot of improvisation, and then working things out from that?

JS: I would just tape every damn thing – I had a DAT player running the whole time. Some of the songs were programmed into a sequencer, and it was programmed and performed live. Some of it was just improv. The last track, the really long ambient thing… that was just one take. That piece of music has been used in loads of commercials and movies. It was just the sound of me letting go in the studio – my statement of what was inspiring me at the time. That was a really busy time, because that’s when I first met Pete Namlook and Move D.

MA: How did the meeting with David come about?

JS: He just turned up in San Francisco and knocked on my door! He said “hey, I’m from Germany, we have a label, we love your label”. It turned out he was on a road trip with Jonas, his partner in Deep Space Network. That night, we went down to see Autechre play their first show in San Francisco. The next day, David came to my studio and did our first Reagenz album. We did it, literally, the day after we met!

MA: You seem to be a natural collaborator. You’ve done loads!

JS: I never managed to find anyone here to work with, and I was always looking for someone to partner with, to start an act. I could always see the potential of a collaborative live thing. To me, human collaboration is often the essence of a great show. Think of John Coltrane and Miles Davis – that’s just an explosive combination.

MA: You also worked with Pete Namlook around that time as well. Did you have to go to Frankfurt to work with him?

JS: He actually reached out to me, because he knew David. I was producing events back then, bringing my favourite artists to San Francisco. I did a show in 1993, and I brought Mixmaster Morris over, for his first U.S show. It was this big ambient event. Then Pete Namlook contacted me and said ‘why didn’t you call me?’ He actually did say that! He just said he would come out and play, would pay his own way, and I wouldn’t have to pay him. He paid to fly out, and arrived with his synth. I felt honoured. I didn’t know him before that, but I was aware of his work. Silence, his great album, was a favourite. What he did at our show became one of his albums.

MA: Returning to the subject of live performance, are you aware how many people there are now – younger artists – who work in a similarly spontaneous way to the way you did in those days, and also perform live shows?

JS: Interesting. I think technology dictates to a large extent what people do. I see that whole Ableton era, between 2002 and 2010, as a black period. Of course, it’s all turned around now. There’s hardware available, being manufactured again and reissued. That’s really changing things, because the gear is now really reliable, unlike vintage gear. You can buy 808 or 303 clones that are exactly the same. Well, not quite the same, but at the end of the day, if you’re doing a gig, nobody cares what the kick drum sounds like, or whether it’s coming out of a TR8 or an 808. It’s still human interaction with a knob or a slider. That’s what’s making the flow of the show – the interaction with the instrument, and the fact that you’re engaging the audience in a much more personal way. They know that what you are doing, you’re not going to do tomorrow night, and you didn’t do it the night before. It’s not like pressing Ableton to playback some loops that you prepared at home. It’s a whole different process from start to finish. That’s what makes it more exciting!

MA: You mentioned earlier that you never got rid of your original synths and drum machines.

JS: Yes, I still use my old gear. I use a combination of new modular kit and my original gear. It’s that man/machine interaction which is far easier to do nowadays. I have little devices to connect things, which I always wish were around back then – synchronisation devices that simply didn’t exist when I started out. I kind of feel that it’s taken me this long to really figure out how to do it. Now, I can get on stage with David – particularly David – I’m so confident. We’ll improvise at sound check, and that will form the basis of the first song. The rest is completely improvised, and spontaneous.

MA: Have you and David had any offers to do Reagenz shows in the UK soon?

MA: Have you and David had any offers to do Reagenz shows in the UK soon?

JS: We have had offers. There’s nothing planned, but it will happen. I’ve been out here putting my kids through college and doing all sorts of stuff. Europe is where it’s at. The business is there and that’s where the gigs are right now, so I have to come over at some point soon. I think next year [2016] we’ll be out there again.

MA: Is there some new Reagenz material due?

JS: We have these shows that we recorded, and we want to try and do something with those shows. We’re just trying to figure out how to do it. I haven’t been to Europe in a while, so haven’t had a chance to get in the studio with David. The studio process is a whole different thing. To be quite honest, I find it really painful being in a studio and doing things using a mouse. It gets really boring.

MA: You do seem to be someone who works best when doing things on the spot, in a hands-on way, with synthesisers and hardware.

JS: Back then I had no choice, though.

MA: Yes, but the point I’m making is that perhaps you’re someone who enjoys spontaneity and works best that way, partly because of your background in live music performance

JS: Definietly. I’m not the guy looking for the software that makes it really easy. It’s about things in the moment. Improvised music is just a whole different thought process. Of course, I do sit in the studio and painstakingly construct things. If I get a good idea, sometimes the only way I can do it is to painstakingly construct it piece by piece in the studio. I’m not some kind of purist, who says it has to be one way. I’ll use whatever it takes to get the idea out – it could be a plug in, whatever. Generally, it all starts by setting out with a bunch of gear. You can’t really do that with software, because software can generally only do one thing at a time. It’s just easier for me to turn on the synths.