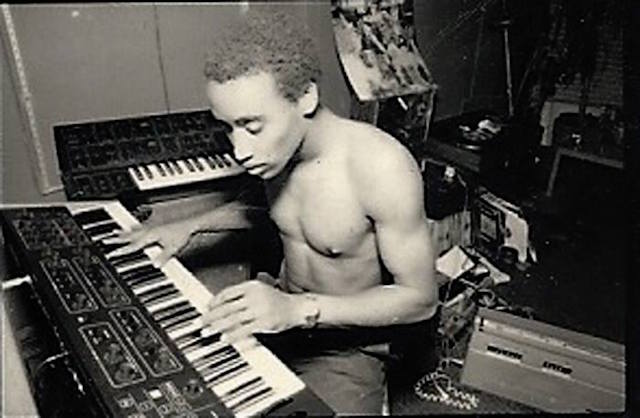

There are few in this world that can say that they genuinely helped forge a musical revolution, but Boyd Jarvis was one of those people.

Waking up to the news of his passing in mid-February 2018, my mind naturally began to wander back to the outstanding dance music he made, often alongside good friend Timmy Regisford, in the early-to-mid 1980s.

Boyd’s death was not a surprise – he had lived a full life, was recently treated for cancer and had battled illness in the past – but it was still acutely felt by many, not just those who had worked with him in the past, but also many thousands of DJs and electronic music enthusiasts around the world who fell in love with the sparse, bassline-fuelled brilliance of the synthesizer-heavy tracks he created during a fertile period in the evolution of dance music. Tracks like Visual’s “The Music Got Me”, Circuit’s “Release The Tension” and Level 3’s “Central Line” – not to mention countless remixes and dance floor dubs – remain near peerless examples of the dubby, “Proto-house” sound Boyd developed with Timmy, Paul Simpson, Winston Jones and others.

I was lucky to have spoken to Boyd at length a couple of years back as part of a feature I wrote for Red Bull Music Academy Daily examining the development and legacy of that New York proto-house sound. When the New York Times recently published an obituary, the newspaper quoted my article.

On the back of that, I decided to dig out the original transcription of our interview, as I was only able to use a relatively small number of quotes from Boyd in the RBMA piece. In it, Boyd talks at length about his life, the innovations and approaches that led to the development of a club-friendly trademark sound, and the battles with drug addiction he and his contemporaries went through in the late 1980s. I’ve decided to make the whole thing available (with the permission of my editors at RBMA) so that more can read Boyd’s story – in his own words.

Matt Anniss

We might as well start by talking about the recent EP that Echovelt put out of unreleased versions of tracks you and Timmy Regisford did with Colonel Abrahams. I particularly enjoyed the demo version of “Release The Tension”, which is very sparse with a haunting version by Colonel.

Boyd Jarvis: “We did that the first time we ever met Colonel. It was like his interview to work with us. Then what happened, later on in life, by the time we had a deal with Fourth & Broadway and Island, the same day we were in the studio supposedly recording Colonel Abrams, he reneged and ended up in some studio with Easy Street Records and doing that ballad, ‘A Table For Two’ … or something like that.”

When was Colonel’s “The Music’s Got Me” made and released, was that before or after?

“That was earlier, just a little after we did ‘The Music’s Got Me’.”

That dropped in 1983, didn’t it?

“Yes. So, when Colonel got out of the deal we were forced to find another singer. I had a guy I was working with, James Dees, so I got him to do the vocal, and ‘Release The Tension’ came out on Island as the first Circuit record.”

https://youtu.be/xkAyZGlMLd4

It’s interesting comparing the two versions – naturally the later Circuit version is a bit more polished.

“Everybody loves the old version with Colonel. It’s still going strong today.”

Let me take you a bit further back in the story. I’m really interested in how you and Timmy ended up making Visual’s “The Music Got Me”, and of course your story leading up to that seminal release on Prelude.

“I think I was either 22 or 23 when I made ‘The Music’s Got Me.’ My background is very complicated. I’m a child product of group homes. I was one of those tear-away kids, running amok, moving around from here to there. I lived in Boston from the ages of 9 to 13, before I returned to New York. When I moved into Lexington Avenue, right down the road from me – on the corner of Lexington and Tomkins Avenue, near Tomkins Park – Crown Heights Affair would practice every other day.

I finally settled down in Hampton Place at 17 years old and started buying a lot of records, taking my equipment out to Ford Green and plugging it into the lamp posts to get electricity. I had huge, big ass speakers, a mixer and a few amplifiers. A lot of people don’t know that I was actually a DJ [before I was a producer] – not in clubs, but at parties and at home.

In 1977 or ‘78, I moved to Hampton Place in Brooklyn, which is near where the Williamsburgh Savings Bank is. I lived a block from there. Ironically, when the Paradise Garage opened, it seemed like everyone who lived in my apartment block was there! That block was full of creative people – musicians, artists, models, designers, percussionists. I had a small Elka synthesizer that I was dibbling and dabbling with. I’d been playing around with keyboards since I was eight years old, when I was living in Boston.

While I was living at Hampton Place, I worked for the Board of Education, driving forklifts in the storeroom, before jumping into fashion. I was trying to be a model, and started doing window displays. I started working for a huge department store called A&S, downtown. I then went on to do my own window displays, and from there – in 1977 – one of my gay friends in the building told me there was a new club opening, called the Paradise Garage. So, of course I got hooked, and was a regular at the Garage from that point onwards.

I met a guy named Mike Stone at the Garage. I don’t know if you know about him, but he opened a place called Melons. He came to me on the dance floor and asked whether I fancied working for him. I was like, ‘Yeah, why not!’ It was a huge club, just as big as the Garage. As a matter of fact, people would go there and then go to the garage, or vice-versa, in the same night. I ended up decorating the venue to begin with, because of my background doing window displays. I had a few jobs at Melons – doorman, decorator, security for the booth, selling Black Beauties and Uppers.

I’d just bought my first synthesizer, which was a Yamaha CS-15, because I was really intrigued by making sounds, programming and sound effects. I bought this thing from a guy called Rick Stevenson, who went on to be one of the big programmers for Roland, Voyager, Oberheim and all that. I only had 500 bucks, so asked him to suggest a good synthesizer for the money that I could do a hell of a lot with. He told me to buy the CS-15 as I wouldn’t be disappointed. I took it home, made a bunch of noises, and drove everybody crazy! It wasn’t music then, it was noise!

As I dibbled and dabbled, I began to learn. One day I asked Mike Stone if I could bring the synthesiser into the club, and play over the DJ. Amazingly, both Mike and the DJ let me do it, and it was nice. One of those nights, in around ‘80 or ’81, Timmy heard me playing. At the time, he was DJing somewhere uptown. He asked whether I fancied playing with him, as he had an audition to do a radio show on WBLS. I couldn’t say no! We started doing this show on Saturdays, and then would do other days as well. It became a big thing. On the back of that we began to get remix jobs, and things like that.

By ‘82 I’d moved from Hampton Place to Clinton Avenue in Brooklyn. I spent a lot of time at Timmy’s house, with my synthesizer in the bedroom, with a drum machine and his reels to reels. It was there where we’d put together a lot of the sets for the radio. Some of those tracks that we were making up became interesting. One of them was the ‘One Love’ instrumental. We were in the house playing it, and it sounded mad!

At that time we didn’t even have a working drum machine. Timmy used to use these special breaks records called ‘Mix Your Own Stars’, which were just drum tracks to help you extend your mixes. I would play over that, and that’s how ‘One Love’ got made. I played this bassline over those drums, and it sounded great. We decided to take it down to Better Days, at one in the morning. The place was packed, but everyone was at the bar, rather than on the dance floor. We gave it to the DJ, he put it on, and immediately everybody ran away from the bars and headed to the dance floor. It blew our minds. We just thought, ‘We’re onto something here.”

The same thing happened with ‘The Music’s Got Me.’ It was all about the bass line. While I was playing it, I had modulation on the bass, which started to sound to me like voices. So I suggested to Timmy that I played the bass line, and we also had vocals copying it over the top. It wasn’t long before the idea starting coming together. We made the first instrumental at Timmy’s, and that was called ‘Stomp (The Music’s Got Me).’ Later we thought of adding the vocals and it became a tune.”

So, how did it become a fully-fledged song?

“By that time, late 1982, I had moved from Melons to Studio 54, and then onto another club. I never played synths in Studio 54, when Kenny Carpenter was playing there, but I sure did in Bonds, where he also played. One day I was down with Mike at the club, and they were auditioning for D-Train with Hubert Eaves. Jason Smith was down there auditioning, and the next person on was James Williams. He got the job with D-Train, and I took Jason! That’s how the full vocal version of ‘The Music’s Got Me’ came together.

Everybody that we were involved with at that time because famous in some way. Me and Timmy were like the root to people wanting to make tracks and follow in our footsteps. Anthony Malloy came out of Visual [where he was doing backing vocals], and went on to do Serious Intention and Temper. It was such a small circle [of people].

When we got the record deal, we didn’t have the vocals at all. We just had the ‘Stomp’ instrumental that Timmy and me had been playing on WBLS. We were little kids, really, not professional at all. We didn’t know about record deals. At the time, Prelude had the hottest shit, so we took it there. Marvin Schlacter took one listen to it and said nothing else but, ‘Yes – go ahead, I’ll give you $5,000 and a contract.’ It was beautiful!”

I spoke to Anthony yesterday, who talked about you in glowing terms. He mentioned that you used to play your synth in clubs, but also that you, Timmy, Kenny, himself and many others involved in this story were ‘club kids’ first and foremost…

“I was a club kid, yes.”

One of the things that always gets me about ‘The Music’s Got Me’ is how different it sounded to everything else when it first came out. Honestly, there was just nothing else like it as far as I can make out.

“I guess that’s the CS-15. Every one of the records we did in the early days used the CS-15 for the bass line. We also had a vibe, and a ragtag, rough edge to what we did – our stuff wasn’t orthodox at all. I wasn’t musical in the classical sense – I play music, but I can’t read it. I can interpret music very well with my hands on the keys. We were just kids, with toys that we were playing with, and it became big!”

Certainly in New York and New Jersey, it became ‘the sound’ for a period of time. One of the things I’m keen to explore in this article is the parrallels with what happened separately, a little later, in Chicago. ‘The Music Got Me’ is almost house music before house music, if that makes sense.

“That’s exactly what it was. When people say to me ‘The Music’s Got Me’ was house, I say it wasn’t. I remember me and Timmy working in his bedroom in ‘82 or so, talking about what we should call this music, as it was a little different to what else was going on. I said to Timmy, ‘We’re making this in the bedroom, let’s call it bedroom music!’ It was just a joke between us, but lo and behold the tag we later got was house music. We didn’t call it that. Now they just tag house onto everything, but in actuality they’re wrong. Some people would tell you that CJ & Company is house, but how could it be? House didn’t exist. When that was made, it was questionable what disco even was. When MFSB made ‘Love Is The Message,’ that wasn’t consciously a disco record.”

It’s what makes the job of a music critic/journalist difficult. Were you really aware…

“[Interjects] I wasn’t aware of anything, I had no idea! [laughs] We definitely had no idea it would be big and that it was the start of a new sound.”

What I was going to ask was whether you were aware of people like Paul Simpson and Winston Jones?

“In this journey with me and Timmy, you’ve got to remember a couple of key facts. By that point, Timmy lived next door to Tony Humphries and his cousin. This was way before anyone was big or well known – very early on. On our journey, with the remixes we were starting to get. We were influenced by people like Patrick Adams and the Peech Boys, particularly ‘Don’t Make Me Wait.’ If you listen to ‘Don’t Make Me Wait,’ and then listen to ‘One Love,’ you can hear the inspiration in there.

https://youtu.be/yK5V7czvpXE

During our journey, Paul Simpson came onto the scene. We started doing mixes with Dave Shaw and also worked with Winston Jones. There was a whole team there – Winston, Paul, Dave Shaw, Terry Burrus, Dave Darlington, Timmy – who were doing these things. Although we were working in different studios, we of course came together. If you look at the Chaka Khan remix album from 1989 and check the credits, you’ll see who’s there. Aside from Timmy, the rest of us were involved. There were so many other records that we did together later in the ’80s, but it all started out between 1983 and ’85.”

The sound we’re talking about – that kind of New York proto-house sound, I guess – changed as it went along…

“Yes. When you look at those records, you can hear the sound depending on what year the record was made. After ‘The Music’s Got Me,’ Winston came with ‘Music Is The Answer’. A little later Anthony broke off to do ‘No Favors,’ then he was with Paul making Serious Intention records. There was a whole slew of shit that me and Paul did together, at the time and later on.

“By the time ’86 came along, I did ‘Nobody’s Business,’ and I started smoking crack. 1986-87 was the worst fucking time of my life, because of the drugs. Everybody tried it; some people got hooked, some people didn’t. Larry [Levan] was always blasted. When me and Timmy made ‘Hey Boy’ for Tammy Lucas and Supertronics, the studio and the label were in the same building – Bench Studios.

When we’d finished making ‘Hey Boy’ with Tammy Lucas, Timmy played it on the radio. Larry [Levan] called me up and told me I had to bring it to him at the Garage that night, so he could play it. So I get the reel, head down to the Garage and take myself into the booth. So I say, ‘Hey Larry,’ and he looks at me with this frown on his face, waves at me and then gets the security guards to escort me from the booth. He was high as a kite, man. He didn’t remember he’d asked me to bring this track down to him. A day or say later he called me to apologise and said how blasted he’d been.

The last time I saw Larry was just before he died. I saw him at a phone booth. He wasn’t looking too good. The AIDS was really kicking in by that point. He loved heroin by then, but he loved every drug. It was so sad. Drugs are everybody’s story. I used to get embarrassed by it, but it’s part of my story, and the American story. One of the doctors who operated on me said you either get hooked on legal drugs or illegal drugs – at that time it was one or the other. But the drugs were a huge part of the story.”

When you were making the records, how influenced were they by what was needed on the dance floor – the DJing side of things? If you ever speak to DJs who were active at the time, they say that it was the Dub mixes that often got the greatest response…

“One of the thing that played the greatest role in that was the record pools. A lot of the stuff that DJs played was actually on reel-to-reel. If you did have a record, it would be a test press, or given to you by the guy who made it. Back then, there was a lot more experimentation in terms of DJing. A lot of DJs would take chances, either playing obscure shit, or versions that were wildly different. The experimental Dubs were part of that. I would hear things in clubs and go, ‘What the hell is that,’ and it would be something the DJ had edited themselves.”

There certainly seemed to be a big dub influence on the production. They were very sparse records, certainly compared to the disco and boogie records that had come before them. I assume that was a deliberate ploy, yes?

“I don’t know whether it was deliberate. I would say it was deliberate to make them more DJ friendly. Having longer intros, breaks and so on gave the DJ more opportunity to mess around and build up the vibe. The extended version was a must thanks to Tom Moulton. In terms of intentionally making them minimal, sparse and heavy, maybe not. Maybe that was just all we had, you know?

One Love’ and ‘The Music’s Got Me’ were just little instrumental dubs. I guess we wetted the appetite by playing those so much on WBLS. The three records that became more critiqued later on, when we re-made them in the studio, were ‘The Music’s Got Me,’ which turned out great, ‘One Love,’ which I hated because I think we lost the energy and the spontaneity of the original, and ‘Release The Tension.’ I love the cleaned-up version, and the demo version. It was a nice little production with some background singers, which was fun.

As a musician, you may never be satisfied. Doing those records again, and taking them to the next level was the idea. We wanted to make a real record that could be played on radio as well as in the clubs. ‘The Music’s Got Me’ was really big in terms of radio promotion. That’s what really made the record well known, because it got so much radio airplay.”

From a listener’s perspective, if you analyze those records – especially the dubs – there are quite a lot of stylistic traits, with extensive use of delay being a major one…

“You think about the time period, and the records that were hot at the time, you had influential records, such as David Joseph’s ‘You Can’t Hide’, Konk, and a number of other records, and they all had their own sparseness to them. It was becoming a DJ’s world, so to speak. Or, more specifically, a DJ/producer’s world. There’s always been a marriage there, between producers and DJs.”

There was always a strong element of soul to what you and your contemporaries were doing in New York in the early to mid ‘80s, too.

“Strafe’s ‘Set It Off’ was around the same time. Who knew how big that was going to be? He didn’t know, either. Sure, he’ll say he had an idea to make a certain sound, which he did using the TR-808, but did he know it was going to be a big, big hit? I don’t think so. We worked towards our tracks being hits. We all used to test the tracks out in the clubs if we had a chance. Quite a few times I took reels down to clubs and asked the DJ to see how it worked on the crowd. That would be gauge to go home and tweak it, go back to the drawing board, or even mix it differently.”

Anthony Malloy told me that the famous ‘Special Remix’ of Serious Intention’s “You Don’t Know” was partly shaped by how Larry Levan used to play the original test pressing versions he was given to play. Anthony says that Paul made the Special Mix based on the way Larry would extend certain parts of the record using two copies, the effects he used, and so on.

“Sometimes we would give Larry, or other DJs, a reel. We’d maybe work it next week, and then work it again, maybe adding some of those double claps that Larry did with the flashback echo on the reel. That happened a few times. I remember people, right back to Russell Simmons, walking through the dance floor carrying reels to the DJ booth. He’d stop and chat and say he was taking a new track to Larry in the booth, and wanted us dancers to let him know how we feel about it on the dance floor. Kenton Nix would do that, too – I heard Taana Gardner’s ‘When You Touch Me’ at the Garage in its’ building stages. There were lots of different mixes played before they settled on the final one. Kenton Nix was tight with Larry, because he worked on building the sound system at The Garage. He’d be there during the daytime, making some speaker cabinets, or re-calibrating the system. He was making records way before me. That was a spark in the back of the mind, in my subconscious, that it was something I wanted to do.”

Did it help that you were an enthusiastic club kid, like many others at the time? Did you have an instinctive feel about what a record should do to please a dancefloor and particularly the one at the Garage?

“Oh yeah. Many times while we were working on a track, we’d throw it on in the living room and throw some shapes! Sometimes when I’m making a track, I’ll close my eyes and think of the dancefloor. You want to hear it out there in the clubs, too. One of the things that was good, that me and Timmy had, was that if he was playing out, we could play our own shit and test it out on the crowd. One time he was playing at a club in Manhattan, and the DJ booth was up on scaffolding above the dancefloor. We rocked that, with me playing live synth – particularly basslines – while he was DJing. You got a chance to develop ideas almost live, and test out things you’d already done, before you even mixed the tracks.

The use of delays on some of the records in that period were something else. Think of the bass line on ‘Don’t Make Me Wait’, the claps on ‘You Don’t Know’, or the distinctive cowbell in ‘Music Is The Answer’. Back then we all knew each other. The first time I met Winston Jones was when he did ‘The Music Is The Answer’ – I was annoyed that he’d stolen Colonel off us. But you just couldn’t deny that ‘Music Is The Answer’ was superb. I worked on a lot of very cool records with Winston after that.

I also love the looseness of the records we’ve been talking about.

“Everything wasn’t locked hard, or synced, like it is know. There was a swing to the tracks, however raw they were.”

I guess that was just a product of those old drum machines wandering in and out of time.

“There was a looseness, yes. Each one was different. I had a DX, and later a DMX, a 707, and a Linn drum machine which woyuld definitely fall in and out of time. The DX was great, but it had a looseness and didn’t feel so tightly quantized.”

When you guys were producing those records, how did you tend to do them – groove first?

“Sometimes. We did a lot of dubbing, too. For ‘The Stomp’ version of ‘The Music’s Got Me,’ that was all overdubs. Even on the version of the record that came out, I played the kick drum by hand on the keyboard. I just fashioned a kick out of white noise and sub frequencies, and played that by hand, throughout the whole record. Then I played the bassline, added the white noise, and overdubbed some synthesiser horn sounds. That was it at the time. Some of that was done by hand – most of it I think. The congas were real, I think, but most of the rest was on the synthesiser.”

There seemed to be more of an influence of dub in the production, certainly in records by Paul Simpson but I’m guessing yourself and Timmy, too.

“Not for me, because I don’t really like reggae that much. I’m not crazy about it. I tell you who I did like, and who were very innovative in their way: Sly and Robbie. They were hugely important, because of the bass and the rhythm. The bass line on ‘Peanut Butter’… mesmerizing.

Very true – that’s an awesome record. It seems from what you’ve been saying that in the early days you did almost everything with one or two synthesizers.

“Once the synthesizer came into play, that changed my world. Let me make a strong point, too. A lot of the people making records at that time were not musicians. That’s another factor that made the music sound like it did. It was because people were piecing things together. By the time we did ‘The Music’s Got Me’ ‘I’d been playing around with keyboards and synthesizers for a few years, but I didn’t consider myself a musician. I played keys, but at the time I couldn’t tell you anything about music terminology.

The synthesizer for me was a window and an opportunity to get into the music business. The drum machines came later for us. I did read books about synthesis and creating sounds, and learned to make drum sounds using white noise, sub noise, click, and so on. Through that I discovered how to make my own syn drums, claps and kick drums. I did a lot of that. I had an AKAI stereo reel-to-reel, which allowed you to dub from A to B, and then from B to A. Once you do your first dub it goes mono. I would just dub back and forth to build a track, before sequencers.

I can tell you right now: Paul Simpson was not a musician. Timmy Regisford was not a musician. Dave Shaw is not a musician. Winston is not a musician. None of those guys were musicians. I got categorised as a musician because I played the lines. They were all great with drum machines. Winston’s speciality was the E-mu SP-12, and he also had a DX, too. We spent a lot of time working together, and we all had our own speciality, so we’d end up on the same tracks. It was always me, Winston, Terry Burrus, Andy Marvel and either Paul Simpson or Dave Shaw. Later, Dave Darlington was the go-to engineer. Other things were done at QUAD or Bassic Studio.”

What happened to Winston Jones? He’s someone I’ve not been able to track down, but would love to talk to.

“I’ve been talking to Dave and Paul, and we’re trying to get him back to do some projects. Winston gave up on the music business a long time ago. Dave did pull him out, maybe seven or eight months ago.”

Anthony told me that he’d either had an email from him, or he’d spoken to him. He just seems to have completely disappeared.

“Anthony is supposed to be getting his ass over here! Pull up a mic and let’s get busy [laughs]”