The Black Dog member Martin Dust launches “Brutal Sheffield” – a unique photobook capturing the stark shapes of his hometown

A denizen of Sheffield, Martin Dust is most definitely a son of the steel city. Having immersed himself headlong in both the graphic arts and electronic music for the best part of 3 decades, there’s no doubting his credentials. He started his professional career as a graphic designer and creative director, working with both local and large international companies where he gained a unique understanding of brand-building through imagery.

Not one for staying static, he’s also been heavily involved in pushing sonic boundaries at the experimental end of IDM/Electronica/Ambient for over 20 years as one third of one of the UK’s most influential outfits, The Black Dog. Universally respected for their classic Parallel, Bytes and Spanners albums which literally created new fields of music back in the 90s – the band’s huge catalogue is testament to their legacy and dedication to shaping sound without prejudice.

An outfit we like to keep tabs on, the recent announcement of Martin’s forthcoming photobook “Brutal Sheffield” peeked our interest to say the least. A pictorial essay that encompasses a wholly unique angle on his hometown, it focuses on the wealth of stark brutalist structures that make up the landscape across the city. We couldn’t help but be drawn in by the magnificence of his take on these wonderfully monolithic, blocky geometric forms. As he puts it: “The book deals with my attempt to come to terms with Sheffield, living and working here, the place I fell in love with, the past, the future and the present.” Far from a nostalgia trip with rose-tinted glasses, the book is as much introspection as it is a celebration and appreciation of the raw form these structures possess.

Curious to find out more about the project, we reached out and put these questions to him:

After several decades of releasing musical projects, tell us about your relationship with visual art and your work…

“I’ve been releasing music since 1979, like almost everyone I started with homemade cassettes and covers. I’ve been in a fair few punk bands and it was always the dream to be on Top of The Pops and have releases on vinyl. I’ve been involved in The Black Dog for the last 22yrs, in 1989 I bought a synth and never looked back.

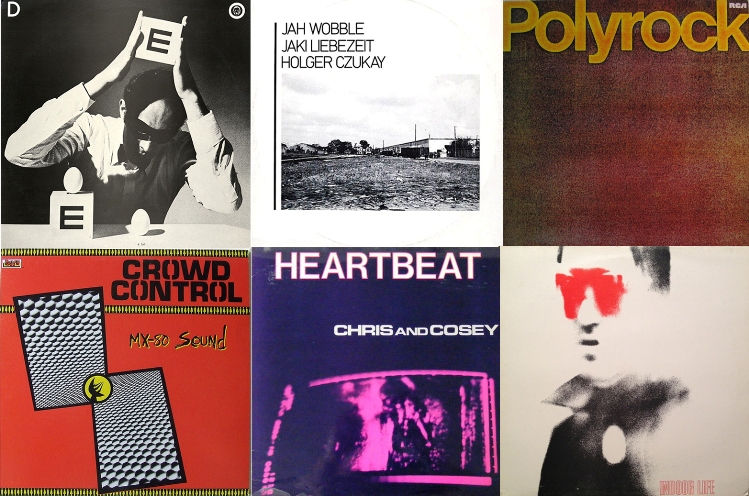

My background is as a graphic designer, so I’ve always had an interest in the arts and artwork, anyone buying vinyl back in the day couldn’t help but have a relationship with it. I do some of the design for our label, Dust Science, but not all of it because I often like a lot of things other people are doing.

As a photographer, I guess I’m just about to say here I am, have a look at my work. It’s been a hard 3 year journey, finding my feet and having enough confidence. It’s completely different from making music, there’s a big difference between taking a photograph and a snap, that line is hard to find sometimes.”

Why did you choose to focus on photography as opposed to moving pictures or animation?

“I’ve written a lot of music for films and been an extra on some of them, I know how much work goes into that and how much ends up on the floor. I think I just wanted to do something on my own, so I could go up the learning curve at my own pace and find my feet alone. I wanted to tell a story in a single frame rather than a movie. I think a lot of people think it’s easy to do movies. What’s easy is writing a good two-paragraph synopsis, the hard bit is doing the rest and there’s no way I’m that arrogant.”

Do you have a particular modus operandi you like to adopt when out with your camera?

“One man and two lenses – is as basic as it gets but I’ve made a lot of mistakes on the way. It’s taken almost 3 years for me to show anyone my work. We (The Black Dog) ended up writing 60 minutes of music for me to listen to while doing shoots, because I need to slow down and stop just collecting things. I needed to find the lines, wait for the sky and the light. It worked and was a massive lesson for me. It stopped me having to go back to places because I’d missed the best shots. I try to find shots that speak about the buildings and the lines that tell a story. It’s much harder than you’d think.”

When did you decide to you were ready to start producing prints and launch a book?

“We’d already been working on an ultra-limited 12” project that comes with a booklet of words and photographs, and out of that came the idea to take some of the pictures and focus on the brutalism of Sheffield. We wanted more than 100 people to see some of the work and I’ve spent almost 1.5 years doing it, so we just said let’s risk it and do a book! On reflection, it’s one hell of a way to announce yourself, but hey, publish and be damned!”

Having spent most of your life in Sheffield, how has this shaped your view of your city?

“I think it informs everything in a way, watching it change and become like most other cities has been painful. I find it ironic that people are now buying my prints of brutalism to hang on their walls, when 20 years ago everyone hated it. I guess the biggest influence is the Sheffield attitude of ‘Go On Then, Impress Me’ and I hope I’ve done that. If not, they can have the other Sheffield attitude and ‘Get Fucked’!”

In what way has this evolved over the last 20+ years?

“I’ve spent months walking the city from one end to the other, it’s changed so much, lots of the small odd places have gone, so have most of the pub. I think it’s losing a lot of individuality and it’s being replaced with pound shops and grey industrial buildings. I think that’s a real shame that they don’t see any value in being different and I struggle with the idea of Sheffield just being like anywhere else.”

How do you feel about the city as it stands today?

“Perplexed by the planners and lack of places for the younger generations to live, practice and play. It feels incredibly short-sighted. We are becoming a city that relies on incoming students, and when they’re not here the city feels empty. I think at the very least someone should be fired.”

And why did you choose to focus on Brutalism as the subject of your first book as opposed to some of the many other angles the city has to offer?

“Like most photographers, you always wonder or look for what your style or thing is, sooner or later it finds you. You just have to keep taking pictures. Brutalism found me and people close by responded to it so much. I had been doing a lot of it. It also helped tell my story of Sheffield because I’d spent so much time in these places.

They always say tell the story you know and I think/hope that’s what I’ve done. I want to find the beauty in a form that’s forgotten, to me it still looks like the future. I really didn’t fancy writing a book about Sheffield United if I’m being honest about it.”

Has it led to you re-evaluate your relationship with your home environment?

“The main thing is how much time has passed and how you only get one go at this thing called life. I’d like to leave a few more fingerprints on things before I go.”

When you see the iconic images taken by Martin Jenkinson in Sheffield in the 80s, how does it make you feel looking back through his lens now?

“Martin came up from London and made Sheffield his home, he worked as a steel worker for many years and for 4 decades he documented the city and people. More than that though, he documented the massive injustice going on at the time. He’s left a massive body of work that is extremely important and powerful, some of those images will last forever and I wish I could say that about just one of my photographs.

I’m not that protective over Sheffield, I believe there is more than one view to be had.”

Who in modern-day terms would you like to see take on the city in that respect?

“I would be interested in someone like Joshua Jackson taking on the city at night. His work in Soho and New York is amazing. Perhaps Sean Tucker doing the street life and local photographer Mick Jones with a medium format camera, his work is brilliant.”

What subject do you see yourself tackling next?

“More brutalism in different places around the world and portraiture, which is something I’m deeply interested in but C19 put a complete stop to my work on that side. I’m currently working on the idea of doing a magazine on brutalism just to feed my habit. As soon as it’s safe enough, I’ll start work again on my portraits. I just don’t have enough work ready to show people at the minute but I’m keen to get going again.”